Research

As part of our mission to preserve and rediscover the historical European martial arts we constantly study and research the subject and its many aspects through a variety of methods and disciplines. This page briefly summarizes some of our key avenues of research and some of our favourite findings and results.

Material study

Understanding weapons is fundamental in a weapons based martial art, so it should come as no surprise that we dedicate a lot of attention to the study of historical weapons! Luckily, we are all fascinated by swords so we certainly don't mind.

Studying and handling historical weapons allows us to better understand how they handle and how they move; details which even nearly perfect replicas may not be able to capture. This informs our study of historical techniques associated with the type of weapon. In fact, an experienced historical fencer is usually able to form an idea of how an unfamiliar weapon can be used based on its handling and its construction.

Detailed analysis of historical pieces also gives manufacturers of training weapons more information to develop their own work, leading to more realistic simulators for our practice.

Below are some examples of our research in this area.

Handling sessions at the Palace Armoury, Valletta

The Palace Armoury in Valletta houses Malta's largest collection of edged weapons, and we are proud to have collaborated with the Armoury on several occasions. These collaborations allowed our students to examine several of these artefacts.

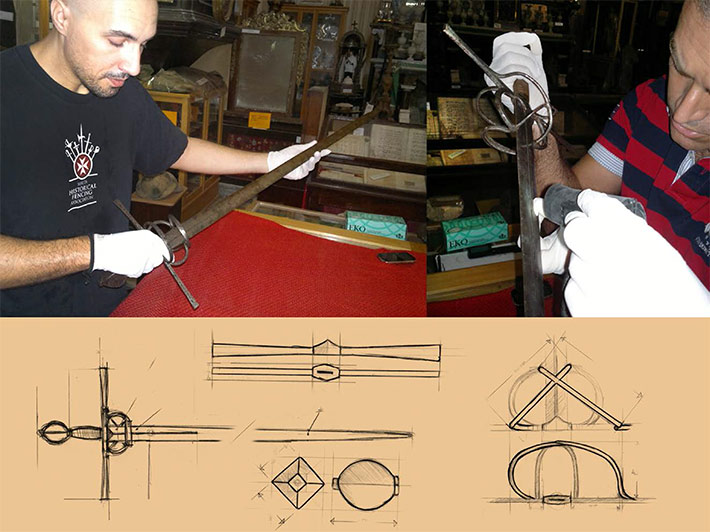

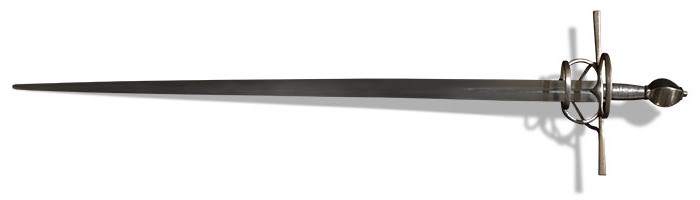

The De Valette Sidesword

In 2012, the Vittoriosa Local Council and the Parish of San Lawrenz kindly granted us the opportunity to inspect the sword of Grandmaster Jean de Valette which is exhibited in the Oratory of St. Joseph in Vittoriosa.

The results of this study were then shared with swordsmith Marco Danelli who was able to create a replica of the weapon which we could use for practice.

You can read more about the sword on our page dedicated to the De Valette Sidesword.

Source material and documentation

All the techniques we study are interpreted from historical sources; training manuals, treatises on fencing, and other documents which were written down by fencing masters throughout history. While a great number of these documents exist they have not been fully explored yet, and we are certain that there are still others which have not yet been rediscovered.

While individual, original examples of these documents are rare and understandably well protected, in the last few decades digital archival of these texts has come forward in leaps and bounds, allowing everyone access to their contents. In addition to facsimiles, several volunteers have also transcribed or translated sections of these texts and made them publicly available either online or in print, making the analysis much easier.

As part of our study, we analyse these texts to understand the techniques and systems described by the authors, with a view to reconstructing them. In most cases, we use facsimiles or transcriptions of the original whenever possible; while translations are invaluable, even the best translations can lose some of the subtle meanings implied in the original text. These changes become reflected in great changes in the execution of the technique.

Apart from these documents, we also study additional historical documentation to help us understand the context in which the weapons were used. This kind of documentation tends to be even more readily available and has already been covered by several historians. This gives us clear indications - or at least, significant clues - as to which weapons were used, when, and in some rare cases even how and when instruction in those weapons occurred.

Collaboration with the National Library of Malta

The collection of the National Library of Malta includes a number of books and archives that were in possession of the Order of St. John at the time it left the Maltese Islands in 1798.

Among these books are a number of fencing manuals, including Di Grassi’s “Ragione di adoprar sicuramente l’Arme, si da offesa come da difesa”, Agrippa’s “Trattato di Scienza D’Arme”, Labat’s “L’art En Fait D’armes”, D’Alessandro’s “Opera di d. Giuseppe D’Alessandro duca di Peschiolanciano divisa in cinque libri”, and Blengini’s “Trattato teorico-pratico di spada e sciabola”. Between them these books span three centuries of the art of fencing, in both civilian and military contexts.

In February 2012, we collaborated with the National Library to set up a public display of these texts. The collaboration included a visit for our students to give them the opportunity to see these texts in the flesh.

Biomechanical study

As with any martial art, historical fencing requires an understanding of human motion and the capabilities of the human body; more so when trying to translate written instructions into actual movement. While a large part of this understanding is gained through practice and experience, we also seek out additional information from practitioners of other martial arts and sport science researchers.

The purpose of this study is to identify the optimal use of position, alignment, and movement to generate force, maintain balance, and protect the body from strain injuries that may occur as a result of movement. While none of the original sources refer to these details, the writers and the original audience of these documents were far more physically practiced than we are today.

Much of this information would have been known to them, albeit not scientifically, as a result of habit or experience, or simply verbally from an instructor. Since the writers assumed that this information would be known to the reader, it is most likely that they chose to omit it to avoid bogging down their text with a large amount of detail their readers would not need, such as the exact angle of the wrist, the exact bend of the knee, the exact alignment of the back, and so forth.

While these may seem to be trivial details, their application can make the difference between a technique being practical or working poorly or not working at all. Additionally, the correct use of one's body helps ensure that one may practice this discipline in the long term.

Collaboration with the Gait Laboratory of the University of Malta

In 2015, we collaborated with the University of Malta's Gait Laboratory to study the force generated during the use of a number of weapons. This study measured both the output - that is, the force generated by the weapon in motion - as well as the where forces are generated through the fencer's body during the execution of various techniques. Of particular note was the amount of force travelling through the neck during cutting actions.

The information from this study can be used to refine our technique training for these weapons, as well as to point out areas we need to focus on with physical training.

The report on this study was presented at the MHFA International Meeting 2015.

Technical Interpretation

Finally and crucially, our analysis of the source material needs to be physically interpreted. While we can never be completely certain that we have understood a technique exactly as the source intended it, testing it out ourselves does give us a degree of confidence that we are at least headed in the right direction!

These interpretations are shared with other members of the Historical Fencing community for further discussion, testing, and tweaking. Different interpretations of the same principles are not just possible, they are amost inevitable and part of a healthy exchange of ideas that drives the field forward.

Even if there is an "accepted" interpretation of a principle, this is by no means set in stone, and we always welcome new research which may shed more light on the subject.

It is important to bear in mind that the point of this interpretation is to get a better understanding of a historical technique, not to create an entirely new one. Doing otherwise would mean that it is no longer a historical study.

Below are some of the interpretations we have researched.

Rapier and Cloak

The use of a cloak for defence is described in a number of sources, although our research focused mainly on the works of Salvatore Fabris and Ridolfo di Capoferro.

Although using a length of cloth to deflect a sword may seem unrealistic - it takes most people some time to trust the cloak to protect them - it is extremely effective and lends itself to some very interesting fighting. Throwing your cloak at your opponents to distract them is also extremely entertaining!

This study was originally presented in a workshop by Mro. Andrei Xuereb at the MHFA international Meeting 2012, and again at the FISAS International Meeting 2015. It has also been incorporated into the MHFA Rapier curriculum.

You can find more information about Rapier and Cloak on our page dedicated to the Rapier.

Sidesword and Shield

While the combination of sword and shield is iconic many of the sources concerning the sidesword focus on dueling and civilian combat, where the scope for a shield is rather limited. However, sources do exist. For our research, we focused on the works of Achille Marozzo, Camillo Agrippa, Ridolfo di Capoferro and Giacomo di Grassi, all of which describe the use of the round shield, or Rotella.

The shield is a game changer as it presents an impenetrable obstacle to an attacker. A well prepared defender is almost impossible to hit, so fighting shielded opponents becomes a case of trying to trick them into moving into an exposed position. All the while trying not to get hit yourself, of course.

This study was originally presented in a workshop by Mro. Andrei Xuereb at the MHFA international Meeting 2015. It has since been incorporated into the MHFA Sidesword curriculum.

You can find more information about Sword and Shield on our page dedicated to the Sidesword.