Historical Fencing

Historical European Martial Arts (HEMA)

“The strength of the sword should be a function of the placement of the blade, not of the brawn of the arm or wrist”Maestro Salvatore Fabris, De lo Schermo, overo Scienza d’Arme, cc. 1606

Historical fencing is the study of the martial arts which were developed and refined over the course of several centuries in Europe. These techniques cover both armed combat, with weapons such as swords, spears, daggers and pole-axes, as well as unarmed combat techniques like grappling or wrestling. Long imagined to be brutish and crude when compared to their eastern counterparts, the rediscovery and interpretation, in the last few decades, of the manuals left by the masters of the time has shown that they were anything but. The martial legacy that these researchers revealed has the same finesse and depth as anything we imagine the eastern arts offer. This is the art we try to recover and learn.

The Art In Malta

With its often troubled history as the crossroads of the Mediterranean, Malta has seen a good cross section of the European techniques practiced on its shores. To take only one period in history as an example, the tenancy of the Order of Saint John brought with it practitioners of the Italian, French, German, Spanish and English schools of the time. This relatively short slice of time already suggests the variety and richness of Malta’s heritage in this respect.

Practice

In order to learn the many techniques, we practice a variety of drills and training exercises based on historical documentation.

These drills are meant to familiarize the practitioner with his weapon, particular situations, and basic tactics. The objective of these exercises is to develop proper technique and enable the practitioner to execute them naturally.

Free Assaults

Once a practitioner has developed these skills sufficiently, he or she may begin to participate in free assaults. An assault is a sparring match where two participants fight each other. These assaults are not choreographed, hence the word free. Nor are they subject to scoring; their purpose is to reinforce proper technique as learnt through the drills.

Safety

Free assaults are contact engagements; that is, both participants attempt to hit their opponent, using all they have learnt and practiced during their training. To ensure safety, we use passive protective equipment such as fencing masks and padded clothing together with weapons built specifically for this purpose made out of blunt metal with buttoned tips. The most important safety devices are, however, common sense, mutual respect, and the knowledge of one’s limits and abilities, the latter being learned and extended by the drills.

Development

“your exercise does well without the art, but the art is not much good without the exercise.”Hanko Dobringer the priest, cc. 1389

Being a rigorous physical activity, Historical fencing will develop agility, in body coordination and precision of motion; speed, in the ability to attack and defend rapidly; strength, in ones muscles and to learn the appropriate amount of force to use; sensitivity, to feel how the opponent is moving through blade or physical contact and to moderate the force with which an attack is delivered; and stamina, in cardiovascular endurance and muscular control. Given the sedentary lifestyle which afflicts so many of us, such exercise is of the utmost benefit.

Our objective is also to develop and stimulate our mental ability. While learning how to apply historical fighting techniques, practitioners will use their wits and mental agility to try and outsmart their opponent in free assaults, which are themselves exercises in quick thinking while remaining calm under pressure.

The Science Of Defence

“Princes and Lords learn to survive with this art, in earnest and in play.”Fechtmeister Sigmund Ringeck, cc. 1440

Historically, the art of hand to hand combat has always been referred to in terms of defense; the term fencing itself, and its variations in different languages, refers to the action of screening or warding blows away from oneself. The emphasis is on the ability to create a consistent defence, increasing one’s chances of survival. While our practice is performed using non-lethal weapons, our training stresses the same principle, the use of technique and strategy to keep out of harm’s way.

This is in contrast to the practice of sports fencing, where participants seek to score points by striking their opponent. In many ways, historical and sports fencing are dissimilar; in particular, playing to the rules of sports fencing encourages participants to attempt actions which would be suicidal in a real life threatening encounter. By contrast, these same rules restrict the use of a number of historical techniques, in the interest of aesthetics and sportsmanship.

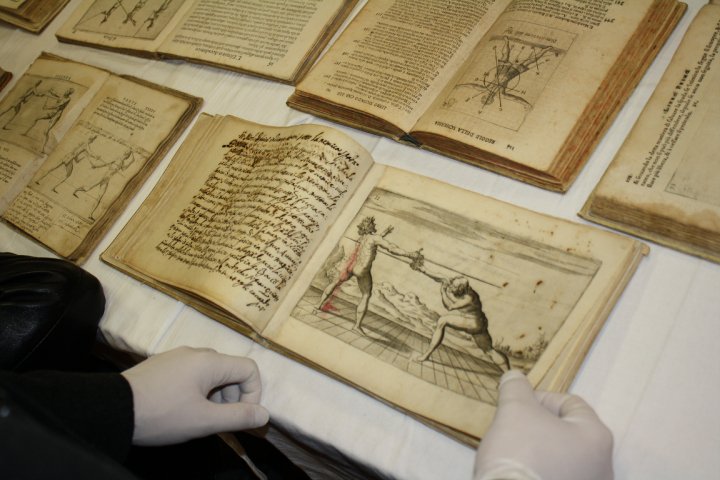

Sources And Research

“because this art is so vast that there is no one in the world who has such a big memory to keep in mind the fourth section of this art without books.”Maestro Fiore Dei Liberi, Flos Duellatorum, cc. 1410

It has been several decades since a sword was last used in a battlefield, and the last duels were only a few years after that. Since the blade was superseded by the gun, the west has largely forgotten it’s extensive hand-to-hand repertoire, which survived only in highly simplified forms, such as competition fencing or theatrical swordplay; in either case, these forms are far removed from real combat.

Unlike their oriental counterparts, the western arts suffered a discontinuity. Until a few years ago, it was impossible to find a teacher to learn from – most people who had been trained to use the sword in earnest had passed on. It is fortunate that many fencing masters left documents detailing their work and techniques, allowing dedicated researchers to reconstruct them.

These documents, the oldest complete one known at this time being dated circa 1290, are a vital resource to the researcher to gain invaluable insight into these techniques. One must, however, bear in mind that many of these treatises, especially the earlier ones, were not intended to be the equivalent of today’s self-training books. Some works are deliberately cryptic; many of the older masters of defence were, after all, in the business of teaching, and it did business little good to give all one’s tricks away to the competition. Others yet may be more or less ambiguous due to the use of language or the nature of the illustrations. Some of these books were produced before perspective or depth were used in depictions; the surprising feature is that they give so much information, not that they are occasionally unclear. In all cases, however, there are strong suggestions that the intention of these works was to serve as a complement to the lessons given by a master; to jog one’s memory for practice, not to replace the teacher entirely.

Given this, anyone trying to reconstruct a technique from a text will find that, beyond a certain point, it is necessary to put down the book and trying it out for themselves. While a considerable body of knowledge has already been built up in this way, experimentation and cross-checking are always encouraged. In this way, the study of historical fencing can be as much an academic pursuit as a physical one.